The global economy enters 2026 in a manner that few would have predicted at the start of 2025: slower, yes, but far from stalling or even contracting. The expected cracks have not turned into fault lines, and the cycle, helped by a supportive policy mix, has absorbed successive shocks. Growth is settling into a low but steady range, inflation is stabilising at lower levels than feared, and labour markets are easing without collapsing. The macro backdrop is not exuberant; it is simply functional – and after the (geo)political shocks of the past few years, that alone feels like an upgrade.

This quiet resilience pushes the global narrative away from recession anxiety toward a world still growing, albeit modestly, and increasingly shaped by structural rather than cyclical forces. It is precisely in this kind of environment – neither booming nor breaking – that markets often climb in ways that feel counterintuitive. Not because conditions are perfect, but because they are good enough to allow risk-taking to reassert itself. And that is how 2026 be.

A World That Refuses to Slow

If the past year has proved anything, it is that the global economy is better at absorbing shocks than at generating recessions. Activity may be softening at the margin, but it is doing so from a position of underlying strength. The probability distribution that investors once feared – a sharp downturn driven by tariffs, policy fragmentation, and rising real rates – has given way to a more balanced profile. The tails have thinned on both sides. The world is neither booming nor breaking; it is simply moving forward.

In this context, the most important macro development of recent months has been the slow but steady improvement in growth expectations. Consumption is proving more resilient than household sentiment, corporate investment is supported by AI capex, and global trade – while still sluggish – has avoided the fracturing many had anticipated. Inflation is normalising, helped by a lower increase in the average US tariffs rate than feared a couple of months ago. Labour markets are softening, but they remain far from fragile. None of this suggests a strong expansion; but, at the same time, all of it argues against contraction.

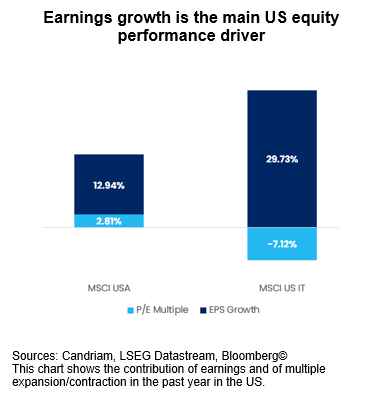

The corporate world is mirroring this macro tone. The earnings cycle has not surged, but it has quietly firmed. What matters at this stage of the business cycle is rather the direction than the level of earnings growth – and the direction is rising again. Earnings revisions, when viewed relative to their long-term trend, are turning positive and accelerating again. The improvement is modest, broad, and consistent with a world where growth is slow but steady. Investors sometimes overlook that earnings revisions have stronger predictive power than headline numbers; in our view, in a low-growth environment, they become the signal that breaks through the noise. The earnings improvement is particularly visible in the heart of the equity market – the US Information Technology sector.

This evolution is particularly important because it comes after a couple of years of extreme volatility in macro data, policy stances, and geopolitical headlines. Markets have had little firm ground to stand on but earnings are now providing that foundation. Corporate balance sheets remain solid, margins have stabilised, and sectors tied to technological rollout, healthcare innovation, and industrial transformation continue to show robust fundamentals.

For investors, the implication is straightforward: equities remain the core risk asset. Not because the world is booming, but because the absence of a downturn is itself a form of resilience. Regional allocation should remain balanced, but the opportunity set broadens as growth becomes less US-centric. Emerging Markets still offer carry and currency leverage; Europe, long dismissed as structurally stagnant, is regaining interest as its policy mix begins to shift and its investment cycle strengthens. In a world that refuses to slow, risk-taking remains our key take-away and justifies our constructive stance on global equities over the medium-term, led by a positive view on all major regions.

The Two Giants and the One Dominant Theme

The defining investment theme of the decade – and of 2025/26 in particular – is the global race to harness the economic power of artificial intelligence. No other force reshapes sectors, reallocates capital, or redefines national strategies in quite the same way. And at the centre of this race stand the two giants: the United States and China.

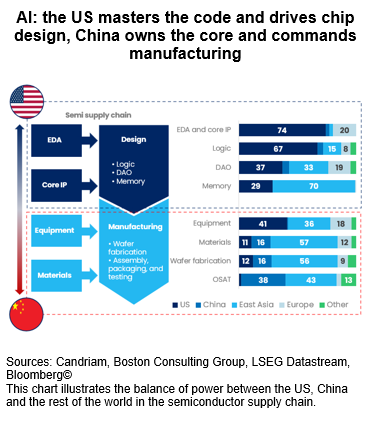

The United States retains a clear lead in AI’s foundational layers — semiconductors, cloud infrastructure, large language models, and software ecosystems. Its innovation engine remains unmatched, fuelled by deep capital markets, dense clusters of human talent, and the commercial dynamism that accelerates adoption. Yet even the US leadership is evolving: the market’s enthusiasm now rests less on headline announcements and more on the durability of the capex cycle that underpins AI’s expansion. Questions around hyperscaler spending, chip supply chains, and profitability are expected – and healthy in our view. They reflect a maturing theme rather than a fading one.

China, for its part, remains a formidable competitor. While weighed down by cyclical pressure and a much slower property-driven growth model, it continues to deploy AI at scale across manufacturing, logistics, e-commerce, and national security. China’s advantage lies in the breadth of its industrial ecosystem and the speed with which it can mobilise resources around strategic priorities. However, its challenge is well known how to balance ambition with structural constraints, notably deflationary pressure and the lingering effects of its real estate adjustment. Yet in AI – and in the broader geopolitical contest it anchors – China’s relevance is not diminishing.

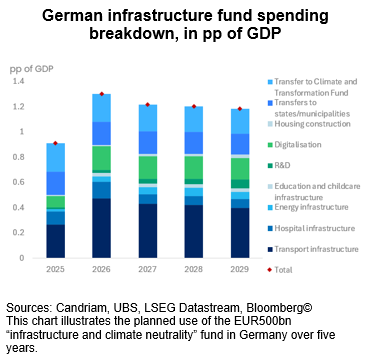

This rivalry is often portrayed as a binary contest because Europe has fallen behind. After years of underinvestment, the continent has barely moved in the face of two rising giants, competing blocs, weaponised supply chains and a steady erosion of competitiveness. Europe has acknowledged – notably through the Draghi report – that protecting its future requires sustained investment, but investors are losing patience as the process proves slow to materialise. The early policy response, particularly in Germany, spans transport infrastructure, energy transition, digitalisation and defence, yet its implementation has been sluggish and may be delivering an economic multiplier below one – more euro spent than growth produced.

This is not a boom story, but it is a recalibration at best. Europe’s decade-long underperformance has left valuations appealing and expectations modest, but it has not yet produced the kind of coordinated investment surge that durably alter the region’s growth potential. The emerging cycle in renewables, grids, telecoms, defence and industrial automation is real, but its impact will be gradual, uneven, and highly policy dependent. It creates opportunities for selective investors – it does not signal a structural renaissance yet.

The Central Bank Backstop returns, and Gold finds its voice again

The final component of the narrative at the turn of the year is policy – and more precisely, the return of the central bank backstop. Not in the sense of unconditional liquidity or crisis-era intervention, but in the form of a stabilising presence that reduces tail risks and anchors expectations.

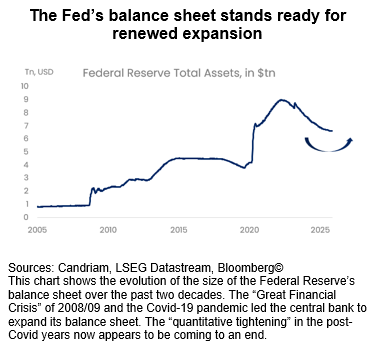

The shift from QT to renewed balance-sheet expansion came fast and forcefully at the December FOMC: the Fed begins buying USD40bn a month in T-bills, with a further USD20-25bn in catch-up purchases if required. The new programme has started on 12 December and restores a pace of liquidity provision not seen in years.

The coming year sits at the intersection of two forces. First, the familiar political cycle: midterm years tend to be the weakest for US equities, particularly in the first half. Historically, though, the same cycle also delivers some of the strongest fourth-quarter rallies, as uncertainty recedes and policy visibility improves. That pattern is unlikely to vanish. The combination of political noise, softer labour data, and uneven consumption could weigh on sentiment during the early months of 2026, before the market regains its footing.

Second, and more importantly, is the evolving stance of central banks. The Federal Reserve has returned to incremental easing, albeit with dissent and debate. The ECB remains steady, signalling that the bar for policy adjustment is higher than before but not immovable. The Bank of Japan continues its long-awaited normalisation. What distinguishes this landscape from earlier cycles is the recognition that monetary policy no longer operates in isolation. Fiscal policy is now a central part of the stabilisation toolkit. Higher structural rates, shifting supply chains, constraints on labour mobility, and the demands of strategic investment require a broader, more coordinated policy response. The next central bank backstop is therefore not purely monetary; it is monetary and fiscal.

This dual support provides a more balanced – and ultimately more credible – anchor for risk assets. It reduces the risk of policy-induced accidents and creates room for the economic cycle to extend, even at low speed. It is not a return to the old playbook; it is the emergence of a new one.

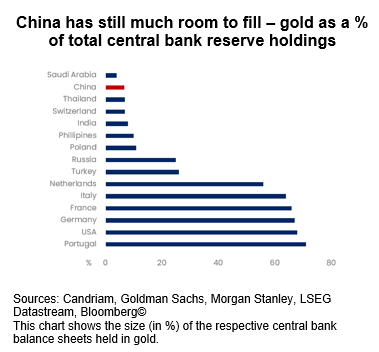

Against this backdrop, gold has reclaimed its strategic role. Central bank demand has surged since 2022, with China in particular accumulating reserves at a pace unprecedented in recent decades. Gold has again become a hedge against geopolitical fragmentation, policy ambiguity, and currency debasement. It is not merely a defensive asset; it is a diversifier for a world in which the rules are evolving and the guardrails are changing. In a portfolio context, it complements equities, EM carry, and core duration – offering protection in an environment where the backstop exists but remains imperfect.

We hold a constructive stance on global equities over the medium-term, and our overall positioning remains Overweight, led by a positive view on all regions.

United States: Slight Overweight: The Fed’s dovish pivot in September has set the stage for further easing. US tech remains a core conviction amid resilient growth.

Japan: Slight Overweight: Trade visibility and tariff relief continue to support cyclical sectors, especially exporters. The election of Sanae Takaichi is symbolizing structural reform and diversity in leadership and is therefore seen as an important step to eliminate the discount on Japanese equities.

Europe: Slight Overweight: Tariff relief offers support, and Germany’s expansionary budget has been approved. The ECB is on hold but retains flexibility.

Emerging Markets: Slight Overweight: Emerging equities benefit from a US -China trade truce until next year, a softer USD and improved trade visibility. EM debt remains slightly overweighed, supported by attractive yields and lower funding costs.

Constructive on duration, particularly in Europe, with a preference for steepeners where policy paths diverge.

Overweight EM debt, supported by real yields, improving flows, and a weaker dollar.

Short USD, with selective long positions in EM FX and a renewed role for the yen.

Maintain exposure to precious metals as a structural hedge.