source: UNEDIC

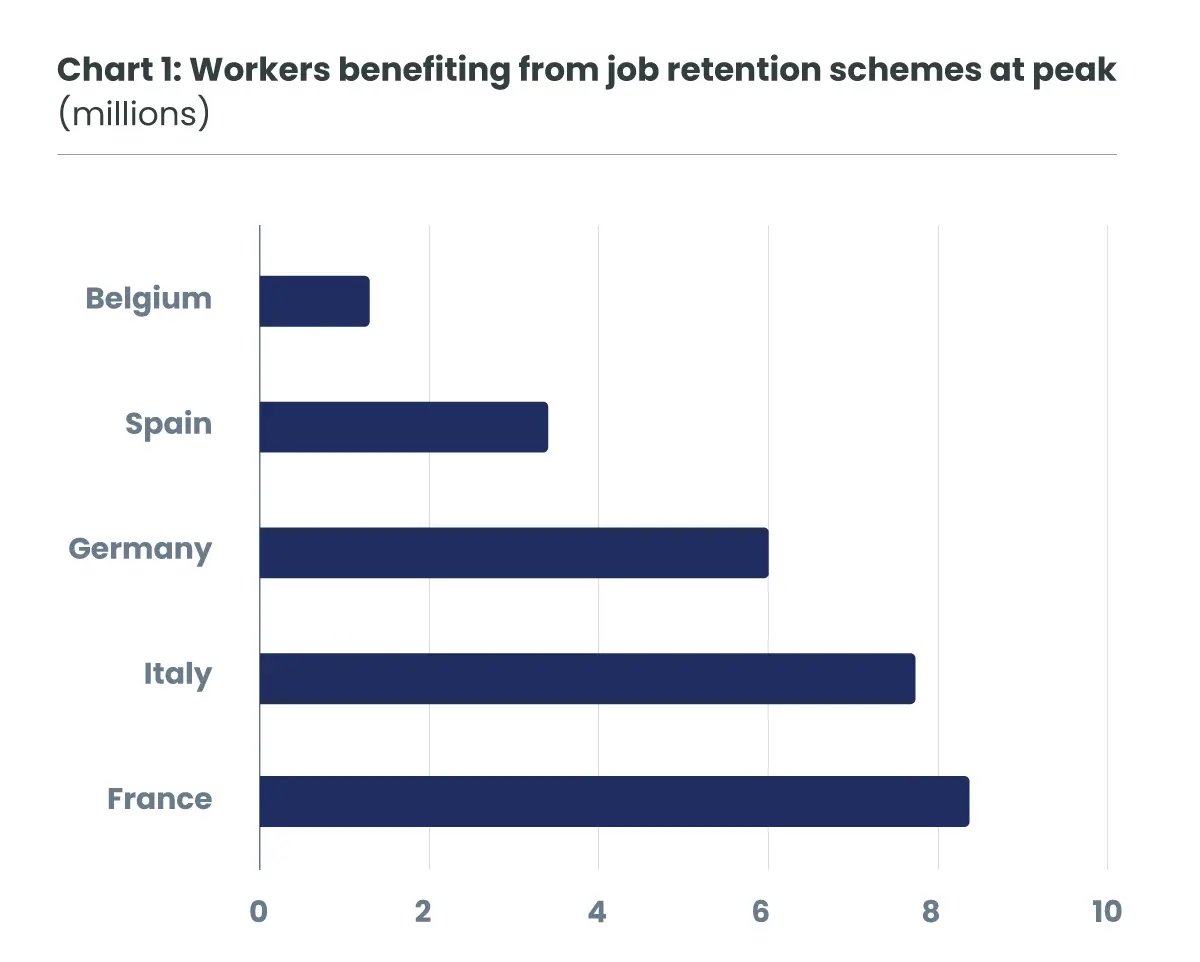

As in the United States, the labour market is tight in the eurozone. However, the nature of the tensions is quite different. While nearly 25 million jobs were destroyed at the height of the pandemic in the USA, the existence of job preservation measures (and the introduction of exceptional measures) in most European countries (short-time working in France, Kurzarbeit in Germany, ERTE in Spain, temporary unemployment in Belgium, etc.) prevented as many jobs from being lost as in the USA (graph 1). On this side of the Atlantic, the period of decontamination was not accompanied by any significant movement of labour, fuelling wage inflation. Nevertheless, companies were soon faced with labour shortages. Initially sector-specific, these recruitment difficulties have gradually spread to the economy as a whole. The reasons for this are unclear: the spread of telecommuting, the reduction in working hours desired by employees, the mismatch between the workforce and the employment needs of companies, etc. Whatever the reasons, it's clear that despite more than a year of stagnating activity, companies are continuing to recruit!

source: UNEDIC

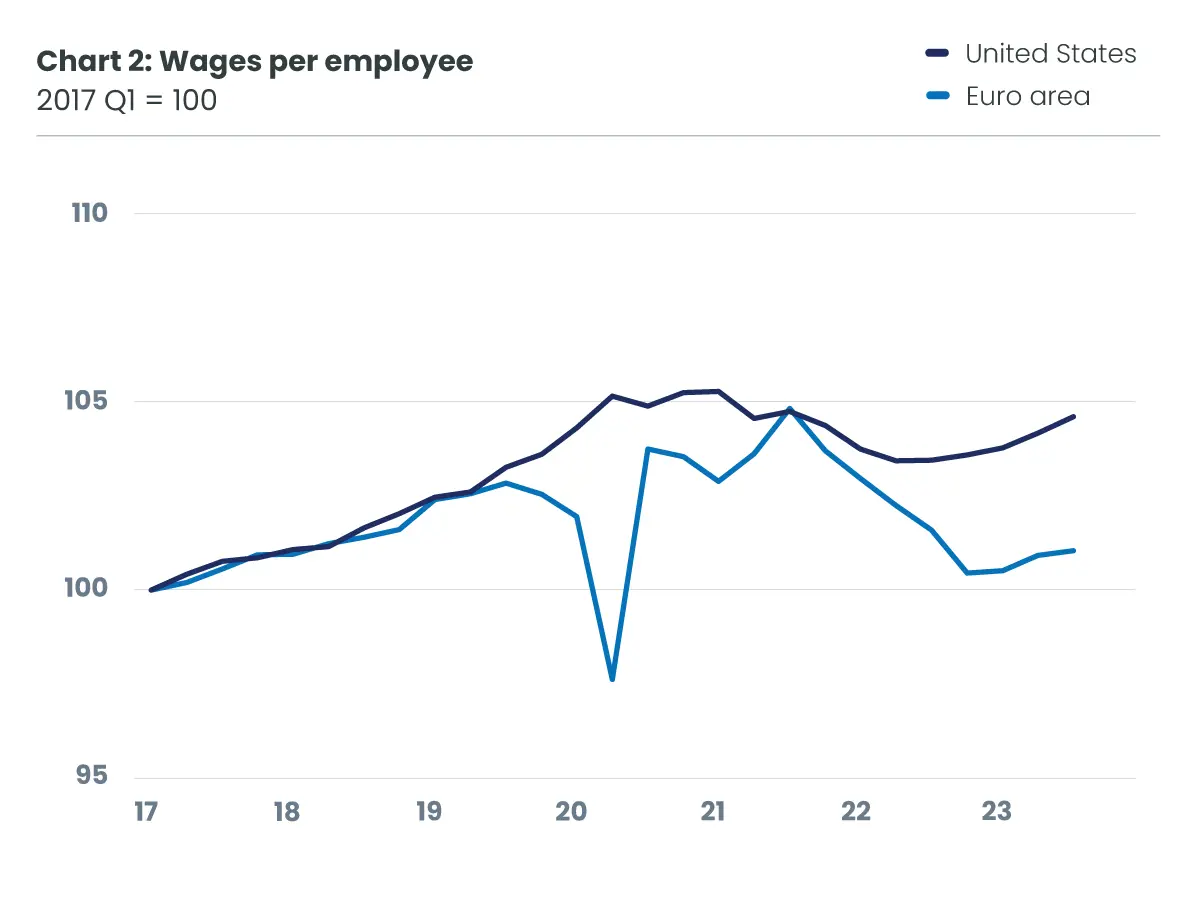

This tight labour market naturally fueled wage demands: wage negotiations across the eurozone resulted in wage increases. So far, however, they have failed to offset the rise in inflation: European employees may now be trying to regain the loss of purchasing power they have suffered (graph 2).

As domestic demand (household consumption in particular) remains sluggish, the risk of these wage increases fuelling a wage-price loop seems limited. The European Central Bank will, of course, remain vigilant to ensure that this wage dynamic does not contribute to destabilizing inflation expectations and fuelling price rises. From this point of view, an easing of labour market conditions would be welcome...