Exiting the pandemic, entering the war and tightening monetary policies around the globe are acting together as a formidable business cycle accelerator. At the turn of the year, reading the economic environment was blurred by the expected re-opening of economies and a somewhat vague commitment by central banks to normalise monetary polices as the impending inflation peak seemed within shouting distance. The various shocks registered over the past weeks have modified – and, to some extent, clarified – the market’s assessment. Our Multi Asset strategy is being adjusted again: we explain why we started to add fixed-income duration after having cut our equity exposure as part of a broadly balanced approach in early-February.

Europe: The war in Ukraine has accelerated the business cycle

The impact of the war between Russia and Ukraine has started to materialise. Among regional divergences, Europe appears the most vulnerable to that shock as the continent is a huge importer of oil and natural gas from Russia. The growth / inflation mix in the Eurozone can be summarised as follows:

Measures taken by governments and accumulated savings during the pandemic could help to cushion the erosion of household purchasing power and allow GDP to grow by 2.9% in 2022. A cut in natural gas delivery from Russia would however represent a major downside risk for growth.

As a result, investors have withdrawn significant amounts from the region: European equities have registered massive outflows over eight consecutive weeks according to Bank of America data. In its recent fund manager survey, 60% of investors said they expected a bear market in 2022 and showed extreme pessimism on global growth. Clearly, discretionary fund managers are not positioned for a rally while the equity positioning of systematic strategies has receded. Conversely, this implies that the overall equity positioning is not supportive of a large immediate draw down in the region.

Inflation is suddenly surging, hitting businesses, consumers and ECB policymakers alike. March inflation came as a shock as Euro area flash estimates posted a 1.8% MoM surge, placing the region on track for an annualised 10% jump in H1-22. Accordingly, the annual rate increased sharply from 5.9% in February to 7.5% YoY in March, exceeding the expected level of 6.7% by a wide margin. There is a risk that it will take much more time than initially expected to see inflation decelerate meaningfully.

- Businesses face new headwinds. The war has suddenly exposed the high level of dependance on Russia and added new disruptions to already strained supply chains. Furthermore, the strong trade interaction between Europe and China is an additional cyclical hit right now: a new outbreak of Omicron and subsequent lockdowns in important cities such as Shenzhen and Shanghai are worsening the slowdown in China and weakening its trade. Finally, the rise in interest rates could mean rising financing costs for businesses in general and for those who have contracted floating-rate loans in particular.

- Households face an unexpected and sudden crunch as war hits purchasing power in an unprecedented way. In addition, initial surveys reveal a significant confidence shock due to uncertainties and the proximity of the Russian war in Ukraine. As identified at the onset of the conflict, the negative feedback loop via different transmission channels (inflation, economic growth, monetary policy reaction and uncertainty) is now underway.

- The change in economic policy instruments to sustain activity implies that fiscal policy will become the main tool engineering accommodation over the coming quarters. There is potential good news on this front as Spain and the Netherlands unexpectedly joined forces recently to call for a renewed suspension of the Stability and Growth Pact in 2023, which would give governments more room for manoeuvre.

- In this context, the position of the European Central Bank (ECB) is not enviable. While downside risks to growth from the war in Ukraine are mounting, the labour market is tighter than ever and inflationary pressures show no sign of abating. Based on the primary objective of the ECB’s monetary policy to maintain price stability (i.e. making sure that inflation remains low, stable and predictable), the ECB will inevitably deliver monetary tightening amid the economic slowdown.

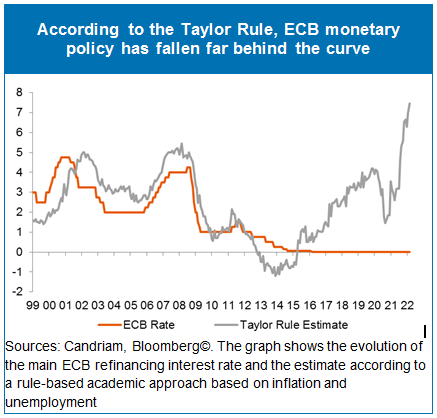

Since the set-up of the ECB and the end of the 1990s, the evolution of the main refinancing interest rate has been broadly in line with the so-called Taylor rule – an estimate according to a rule-based academic approach taking inflation and unemployment into account. Deviations have been rather limited for nearly two decades, although uncertainties linked to Brexit and the pandemic led the central bank to keep its reference rate zero-bound. The acceleration in prices, fuelled by the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, has now opened an unprecedented gap.

Since the set-up of the ECB and the end of the 1990s, the evolution of the main refinancing interest rate has been broadly in line with the so-called Taylor rule – an estimate according to a rule-based academic approach taking inflation and unemployment into account. Deviations have been rather limited for nearly two decades, although uncertainties linked to Brexit and the pandemic led the central bank to keep its reference rate zero-bound. The acceleration in prices, fuelled by the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, has now opened an unprecedented gap.As a result of the current central bank inaction, European (and Japanese) equities still look attractively valued relative to bonds, while this is no longer the case in the US. As shown below, the US central bank reaction function has now largely been priced in by fixed-income markets.

US: Can inflation cool without a recession?

In our central scenario for the US, the recovery progressively slows down to 2.7% GDP growth this year and 1.5% next year under the impact of various factors: higher rates, high inflation, a volatile stock market and a negative fiscal impulse. The Federal Reserve has made clear that it wants to frontload its tightening as long as there are no clear signs of a forthcoming deceleration of growth.

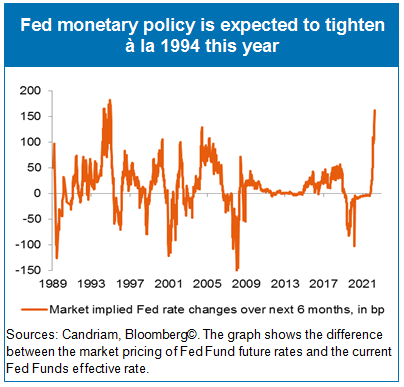

The bond markets have adapted to this approach by the Federal Reserve to quickly normalise, and then tighten, monetary policy to cool down inflation from uncomfortably high levels. Successive speeches by Fed Chair Jerome Powell and Governor Lael Brainard have made clear that the central bank wants to reduce its bond holdings quickly and increase its funds rate fast.

The interest rate markets are pricing a 280bp hike in the Fed Funds rate until autumn 2023, of which 160bp in the next 6 months, a tightening pace last seen in 1994. Hence, there is limited scope for new negative news and further hawkish Fed re-pricing, which is potentially good news.

Soft or hard?

As monetary policy is set to tighten sharply and with the end of the substantial pandemic measures expected to lead to a significant fiscal drag this year and next, we are scrutinising signs to characterise the forthcoming US growth deceleration.

- Despite decent wage inflation (5.6% YoY in average hourly earnings in March), US households register real wages in deeply negative territory. It should therefore come as no surprise that household surveys indicate an erosion of confidence in their personal financials: outside the post-Lehman Great Financial Crisis and its aftermath, one has to go back to December 1990 or even April 1981 to see levels as depressed as today. For now, households have cushioned the sharp drop in purchasing power from rising prices by rapidly reducing their savings rate to 6.3%.

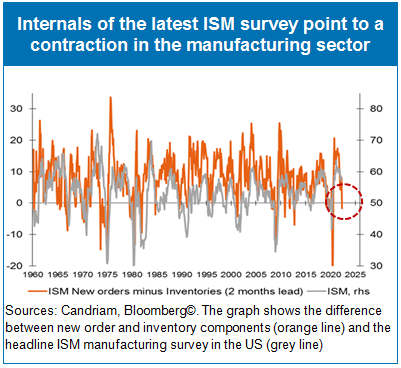

- Regarding manufacturing business, most countries are now experiencing a slowdown in the manufacturing cycle. The global manufacturing PMI peaked one year ago and has been losing momentum since August. New uncertainties regarding the increase in commodity prices are coming on top of the drag from supply chain disruption.

We note that the internals of the most recent ISM manufacturing survey (namely the difference between new orders and inventories) have turned negative for the first time since the pandemic. Over more than 6 decades, this has happened in only 94 occurences, or 12.5% of the time. It has been a reliable leading indicator of the overall direction of the ISM manufacturing index since 1960. The current level is consistent with a decline below 50pt in the ISM Manufacturing Index this summer i.e. a contraction in the manufacturing cycle. Also, the pandemic-linked hiatus between new orders and bond yields has finally been corrected – again, the current level is consistent with a stabilisation in the US 10y bond yield.

Our current multi-asset strategy

The equity markets have been resilient despite these late cycle signs. In order to see equities weaken, we will probably have to see either clearly weak fundamental data or the Fed acting fast and “walking the talk” by removing accommodation or lowering its corporate guidance for the upcoming earnings season.

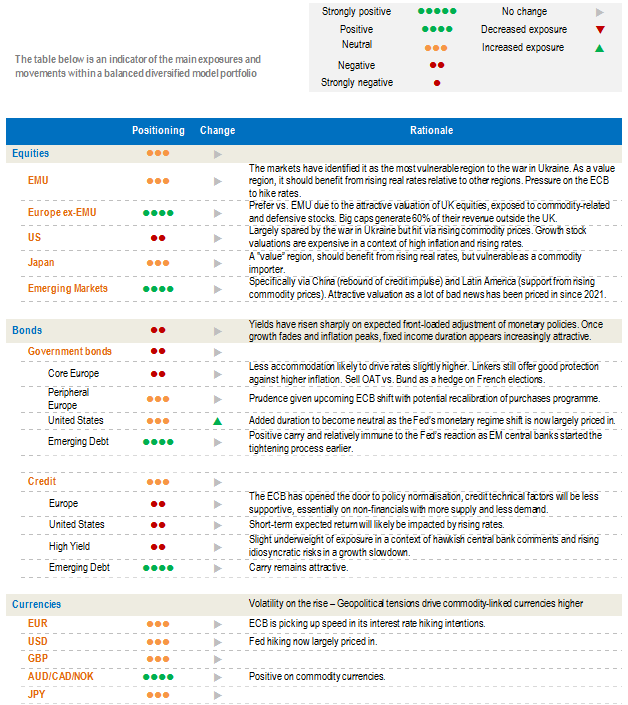

Our multi-asset strategy has started to take into account the acceleration towards the cycle end: we reduced our equity exposure in early February and will stay neutral on equities with some exposure to commodities, including gold. We are underweight in US equities as we see growth stock valuations at risk in a context of rising inflation and rates. Conversely, we are overweight in emerging markets, specifically via China (rebound of credit impulse) and Latin America (support from rising commodity prices).

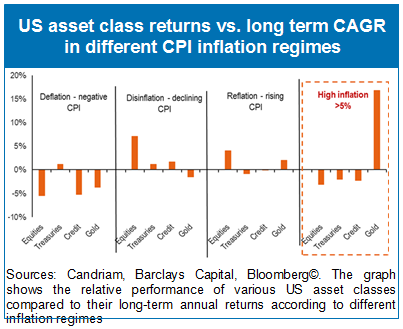

Tactically, equities could benefit from short-term tailwinds as sentiment and positionings have already been hit. However, the longer-term outlook for equities is deteriorating as revenues, margins and, ultimately, profits should be revised lower due to high inflation. Historically, inflation above 5% has led to weak equity performance. Therefore, we will chase market rallies to further reduce equity exposure in our portfolio.

Our current multi-asset strategy

As we expect growth to fade, and with high inflation expectations and central banks willing to tighten, longer fixed income duration appears increasingly attractive. We have therefore increased duration by half a year and continue to diversify among inflation-linked bonds and to source carry via emerging debt.

In our currency strategy, we have exposure to the CAD, which plays a role as a commodity currency, and have taken profit on the NOK, which appears less attractive as the Norges Bank has positioned itself as a seller for the fist time since 2013.