Considered as a global public health priority by the World Health Organisation (“WHO”), vaccinating against human papillomavirus considerably reduces the mortality risk from cervical cancer. This disease could even be partially eradicated if certain restrictions are lifted. Alongside wider screening procedures, broader improved vaccination coverage could also provide further vital leverage.

Acute viral infections are directly involved in the development of certain tumours. Like the early detection of initial symptoms, vaccination may play a decisive role in the fight against the “disease of the century”. Several prophylactic vaccines already provide partial or total protection against the onset of liver and cervical cancer. Although they do not directly treat these pathologies, they nonetheless contribute to protecting populations, by preventing the potentially fatal consequences of hepatitis B and human papillomavirus, in their most virulent forms, with HPV 16 and 18 causing 70% of cancers and precancerous lesions of the cervix.

As the 4th most common form of cancer among women, cervical cancer causes 310,000 deaths per year, chiefly in countries with low or medium average incomes. According to the IARC1, incidence frequency remains a concern, with 570,000 new cases diagnosed in 2018. Epidemiological projections are equally worrying. Without any remedial action, this disease could lead to 460,000 deaths annually by 2040. The problem is effectively twice as bad however. In addition to avoiding deaths, vaccination against human papillomavirus is all the more vital as HPV infection can cause other forms of cancers, in both women and men.

A “safe, efficient and indispensable” vaccine

During World Cancer Day on 4 February 2019, the WHO launched an international appeal to encourage countries to vaccinate girls between 9 and 14 years old against human papillomavirus and also to systematically screen and treat precancerous lesions among women over 30.

Citing statistical proof, the IARC then highlighted that 3 of the existing vaccines2 are “safe, efficient and indispensable for eradicating cervical cancer”, refuting the rumours and controversies claiming that the products in question are harmful.

The IARC had based its findings on the broad perspective it enjoys and also drew on tangible proof to back its claim. Public vaccination campaigns are currently in force in 82 countries. A similar process was initiated over 10 years ago in the US, Germany, Australia, Belgium, Canada, Spain, France and Italy. Since the first reference vaccine was approved in 2006, over 270 million doses have been given to more than 60 million people. No serious harmful side effects associated with the recommended products have been identified by the WHO so far.

As well as noting an absence of the harmful side effects highlighted by anti-vaccine campaigners, the WHO has also observed a positive effect in terms of population protection, announcing that “several countries have notified a 50% fall in the incidence of precancerous cervical lesions among young women”.

Convincing results

Spectacular results have been recorded in some parts of the world, such as Australia. According to the results of research financed by the Australian health authority, the proportion of young women aged 18-24 infected with the 2 main HPV viruses (16 and 18) has drastically diminished over the past 10 years. Estimated at 23% in 2005, the incdence fell to 1% by 2015. With optimal vaccination coverage, further infection by the virus should soon be halted according to the latest epidemiological modelling research. In less than 20 years, there could be practically no new cases of cervical cancer. Technically, these results are likely to be due to the free vaccination campaign launched 12 years ago among 12 and 13 year old girls, which was extended to boys in 2013.

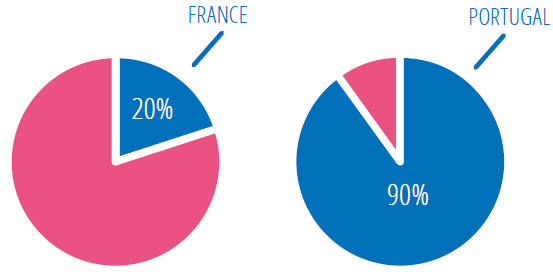

The results reported in Europe are less categorical. Although 37 out of 53 countries on the continent vaccinate systematically, vaccination coverage among the target population (girls aged 9 - 14) varies considerably between the countries, with some broad discrepancies. Vaccination coverage is very high in Portugal (90%), whereas it is very low in France (20%), which ranks at the bottom of the league table.

Vaccination coverage among the target population

There are even greater disparities internationally. The WHO expresses its disappointment that “countries with the highest risk of cervical cancer are also those where the probability of anti-HPV vaccination being implemented is the lowest”.

Complementary measures

Several complementary measures are envisaged to reduce the mortality rate associated with this type of cancer. According to certain experts, implementing organised vaccination programmes in schools could improve vaccination coverage and reduce social inequality by covering a wider population, as demonstrated by the Australian, Canadian and Swedish examples. Vaccination for young boys, currently practised in around 20 countries, could also contribute to curbing the spread of papillomavirus. Direct benefits have already been observed in Australia, Austria, the US, Sweden and Switzerland. In France, although consideration on this front has been slower, the latest signals have been relatively encouraging. A public thematic consultation programme has recently been launched by the High Authority of Health, which is the final stage prior to the publication of an official recommendation.

However efficient it may be, vaccination is insufficient on its own. It cannot take the place of Pap smear testing and the treatment of precancerous lesions, as the WHO regularly reiterates. A recent study3 concluded that the immediate generalisation of vaccination and screening could eliminate almost all cervical cancer across all developed countries within 50 years, and worldwide by the end of the century.

The economic issues at stake are enormous. Although there has been no official data published, overall annual costs for cervical cancer exceed $100 billion. One thing is sure however, primary (vaccination) and secondary (screening) prevention would generate a considerable cost savings for countries, with extremely beneficial results in terms of public health. Prevention is therefore a precious step towards the universal goal we all share, i.e. to contribute to a longer and healthier life.

Liver cancer: the demonstratrable benefits of vaccination against the hepatitis B virus

According to the IARC1, 841,080 liver cancers were detected in 2018. With 781,631 deaths recorded last year, it is the fourth most frequent type of cancer death worldwide. Hepatitis B complications, which are partly responsible for this pathology, can easily be prevented through the use of a vaccine providing almost full protection against the virus (98 -100%). It is recommend for infants, children, adolescents and certain adult populations, including transfusion recipients and transplant and dialysis patients or people involved in high risk sexual practices. Medical practitioners and personnel exposed to blood or blood products in the workplace are also candidates.

According to the WHO, the vaccine showed excellent results in safety and efficiency. Since 1982, over one billion doses have been given worldwide, producing tangible results among infants, with infant vaccination coverage estimated at 84% in 2017. In many countries, the chronic infection rate has now fallen below 1% among immunised children. Such a high level of progress has been recorded that, due to the widespread use of the vaccine, the hepatitis B virus could be eradicated by 2030. It is expected this could also partially contribute to a reduction of liver cancer mortality. Although an ambitious goal, it is nonetheless considered achievable by the WHO, which has included this battle among its priorities.

1. International Agency for Research on Cancer – IARC

2. Gardasil, Cervarix and Gardasil 9.

3. ‘‘Impact of scaled up human papillomavirus vaccination and cervical screening and the potential for global elimination of cervical cancer in 181 countries, 2020-99: a modelling study’’, The Lancet Oncology (February 2019).