How can Sovereign Sustainability help my investment decision-making?

Vincent: Water shortages, climate change, rising conflicts and declining democracy, damage to habitats, energy policies, and other issues of sustainability are becoming geopolitical flashpoints. The interconnections are strong and complex.

For instance, considering the automotive conundrum. China dominates the entire value chain for electric transport motors. The European Union has imposed provisional tariffs to protect its regional auto industry from ‘dumping’, or unfair pricing, of subsidized electric vehicle imports from China. Yet the EU is actively attempting to accelerate the uptake of EVs to meet its 2035 emissions targets.

Analysing factors such as governance, rule of law, and social capital can help identify and price risks, and help predict potential deterioration in sovereign credits – not only through inability to repay debt, but through potential unwillingness to honour it. For example, because we believe that autocratic nations are not sustainable, and their debt carries extra risks, we analysed in 2022, bond performance of nations according their Freedom House ratings of Free, Partially Free, or Not Free. Our results showed that in isolation, this particular element of the data used by our model could produce modest debt outperformance for the “free countries”.[1]

What changes have you seen recently?

Vincent: We can answer that in two ways, in terms of underlying trends, and in terms of country sustainability rankings.

The most notable trends should be no surprise to anyone – we need no numerical indicators of deteriorating democracy or rising conflicts to tell us what we see in the news, although Freedom House indicators (which are part of our model) and national security data trends are indeed declining. Given the interlinkages among nations and topics, what is revealing about our model is the ability to isolate data sets or groups of data which can provide further insight. For example, our model is showing ‘stickiness’ in adoption of renewable electricity generation, despite the frequent cost advantage renewables often hold over new fossil installations; this frequently resulting from bottlenecks in distribution grids with countries at different steps of development: Gulf Cooperation Council countries, particularly Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Oman, and Qatar, are increasing their renewable energy capacity. While their overall renewable energy scores remain very low compared to global peers, these nations are making substantial investments in renewable energy infrastructure. Latin American countries are experiencing the most negative trends, primarily driven by a struggling business environment and increasing tail risks, especially natural hazards.

As to rankings, the largest recent improvements have been in small countries with limited interest to investors. Among the investible countries, we saw a few drops, notably in France, Saudi, and Vietnam, all three suffering from worsening Social Capital scores, among other reasons. India rose a few steps, mostly from an improved Economic Capital score.

What makes Candriam’s approach different?

Vincent: We believe two things make our model investment-relevant and potentially performance-enhancing across a number of asset segments.

- Because Natural Capital is finite, our score calculation constrains the overall score from rising when Economic or other capitals are improved by depleting non-renewable resources. That is, Natural Capital cannot be substituted by other capitals.

- We adapt the materiality of the data to the developmental stage of each individual nation. For example, data on electric vehicles carries much more weight in the score of a country such as Norway, while it tells us little about Uganda, where food security is more relevant to the sustainability of the country. This allows us to compare across all nations, because we do not use an arbitrary break between developed and developing nations.

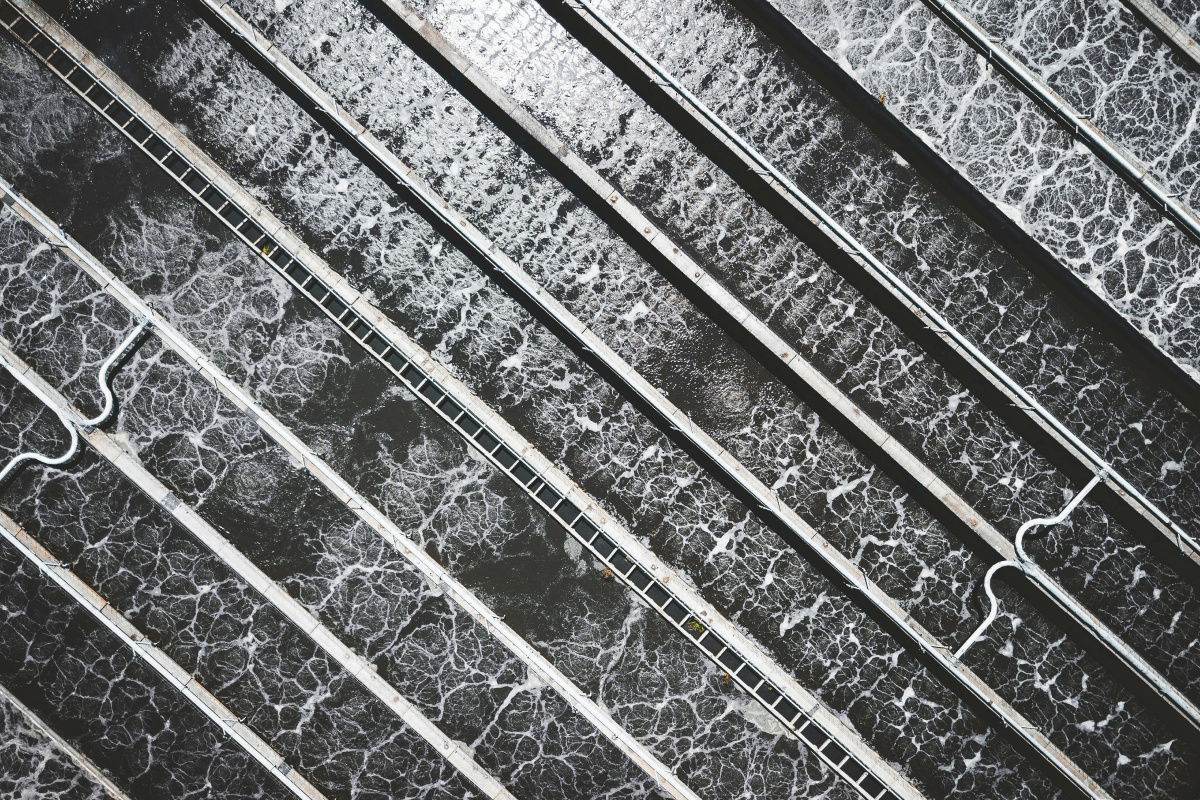

By linking the materiality of the weightings to the constraint on substitutability of Natural Capital, our scoring links short-term and long-term. We have had a sovereign sustainability analysis in place since 2009, establishing a four-capital-pillar model in 2017 and emphasizing Natural Capital since 2020. We continue to move our approach forward with adjustments and additional indicators. Among the new metrics we added this year were several water-related metrics including agricultural risk, food supply, and food affordability.

Why do you say ‘performance relevant’?

Vincent: Isn’t that the goal?

One of the ways we use our model is to help determine which sovereigns to include in our sustainable investment universe. [2] Of course the common view is that any reduction in universe – that is, reduction in choices available to a portfolio manager – automatically reduces performance. We do not subscribe to this view, because we believe our ‘reduction’ methods remove some downside risks.

We recently back-tested our sustainable sovereign investment universe against the broad JP Morgan Emerging Markets Bond Index Global Diversifed™ index (EMBIGD) over the eleven years for which we had a sizeable sustainable sovereign universe (April 2013 to July 2024). Of the 70 names in the EMBIGD index, as of September 2024, we consider 46 sustainable – a one-third reduction. We found that over the eleven-year period, our Candriam sustainable sovereign EM Debt universe performed roughly in line with the larger EMBIGD universe – actually about bps per annum of outperformance, which is not statistically significant.[3] Happily, there were no dramatic outperformances or underperformances when the long term period was broken into annual performances.

How do you use your model in your own decision-making?

Vincent: We use the model as a starting point for additional analysis or engagement. We are actually more interested in the components and component trends within a country’s Candriam model score than we are in its specific score or ranking. For example, just before the 2020 US Presidential election, news headlines prompted us to look at the long-term historical trend of our democracy and political stability sub scores. The US had been deteriorating relative to the rest of the developed world for more than a decade before the 2020 election.

While engagement with sovereigns typically occurs through collaborative efforts, we recently engaged directly and successfully with Costa Rica on their money-laundering policies.[4]

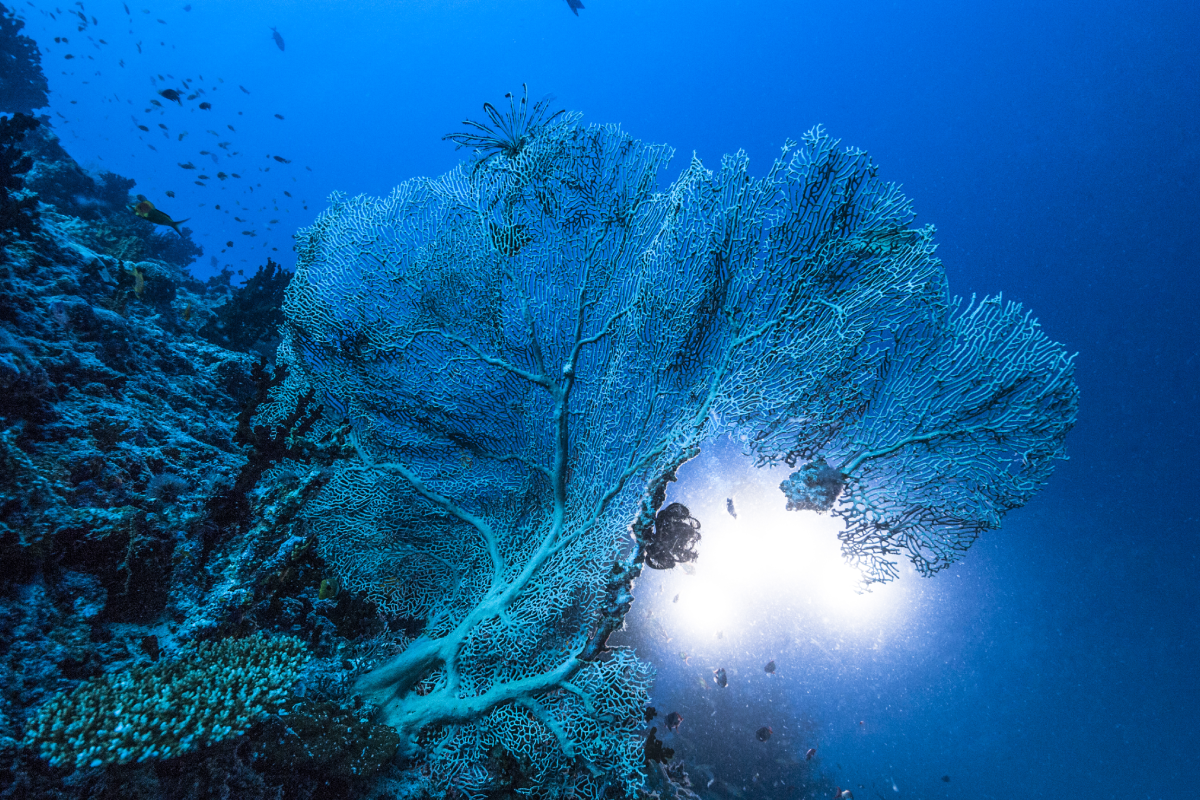

Our framework also allows us to isolate a factor and look across nations – as we did for current instances of water stress, and for water vulnerability (the potential influence of climate change on available water).

Company analysis can also benefit from an understanding of the sustainability of the home country, and an understanding of country risks. A host country with high levels of corruption poses a risk to companies doing business there. Conversely, companies based in sustainable nations can enjoy more predictable operating environments and more support from their home government.

Why water?

Vincent: The state of global water resources is possibly the most urgent of the major threats to sustainable development and the well-being of humankind. Greenhouse gas emissions and global warming are our greatest long-term sustainability threat, but the full impact is more likely to be seen in 2030 through 2050, while regional water crises are upon us today. Of course the topic of ‘water resources’ crosses multiple dimensions, including water scarcity today, water vulnerability to climate change, and the quality of water. Where water pollution combines with water vulnerability, access to water may be choked off. That’s among the reasons we launched a water investment strategy in 2023, and why the Candriam Institute is involved in projects such as Join For Water and WeForest

[1]The scenarios and data presented in are an estimate based on evidence from the past, are not an exact indicator, and are no promise of future performance. Performance of emerging market government bonds from April 2006 to September 2022, using the JP Morgan Emerging Markets Bond Index Global Diversifed™ index (EMBIGD) as a market proxy. “Free” countries outperformed by an average of 30 bps per year over the period.

[2]We use the JP Morgan Emerging Markets Bond Index Global Diversifed™ as a reference. By number of issuers, this is a one-third reduction, by weight, it is a 47% reduction.

[3] The universe was revised periodically, typically annually. The figures of 46 issuers in the Candriam sustainable sovereign EM universe and 70 in the EMBIGD index are as of September, 2024.

[4] For details, read our case study, Costa Rica – Active Engagement, May 2024.