Over the years, central bank independence has become the norm: it is seen as a safeguard against governments that might prioritise growth at the expense of price stability. History reminds us, however, that the missions of central banks have evolved over time and that the importance of their independence has not always been obvious.

The Fed Breaks Free: the Accord of 1951

The independence of the Federal Reserve in particular was wrested away in the early 1950s after a tug-of-war between President Harry Truman and Marriner Eccles, then a member of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors and a long-time chairman. To help finance the war effort, the central bank agreed in 1941 to intervene to keep the rate on Treasury bills at 0.375% and that on long-term government bonds between 2% and 2.5%, a ceiling that the heavily indebted Treasury hoped would be extended after the war. Faced with the return of inflation -- the end of price controls in 1946 and the Korean War pushed it above 20% in early 1951 -- the Federal Reserve wanted to regain its autonomy: The 1951 agreement signed with the Treasury put an end to the "fiscal dominance" regime and laid the foundations for modern monetary policy. The Fed's independence was once again put to the test in the early 1970s. Before the 1972 election, President Nixon pressured then-Fed Chairman Arthur Burns to pursue a more accommodative monetary policy. This episode is often put forward to explain the inflationary excesses of the 1970s. It was followed by a deep recession in the early 1980s provoked by Chairman Paul Volcker in his effort to regain control of inflation. In the 21st century, Chairman Ben Bernanke would draw a clear lesson from this history: “political interference in monetary policy can generate undesirable boom-bust cycles that ultimately lead to both a less-stable economy and higher inflation.”[1]

A new tug-of-war between the executive branch and the Fed

Nevertheless, the Trump Administration seems ready to engage in a new tug-of-war with the central bank. Almost unnoticed, an initial battle to relax banking supervision got quickly underway. Even before President Trump took office, Fed Vice Chairman in charge of banking supervision Michael Barr resigned from his post to avoid a legal showdown over whether the President could fire him. He nevertheless remained a member of the Fed Board of Governors.

Donald Trump's scathing criticism of the Federal Reserve Chairman -- "incompetent", "stubborn moron", "Too-Late-Powell" -- received more media coverage. The aim is to put pressure on Jerome Powell to cut rates faster and deeper. It has to be said that the erosion of household purchasing power caused by higher customs duties is a serious brake on activity: too sharp a slowdown before the mid-term elections would be ill-timed. Having failed to remove Powell without undermining market confidence, the Trump Administration is now aiming to replace other members of the Board of Governors. The temporary appointment of Stephen Miran in September, then Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers, was a first step. The attempt to oust Lisa Cook seeks to speed up the process. If the Supreme Court rules in Donald Trump's favour next January, the White House will have a majority on the Board of Governors, enabling it to remove the Presidents of the twelve regional federal reserves who do not share the Administration's views on the future direction of monetary policy. This could be accomplished as soon as February. The executive branch could thus take control of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC).

If Lisa Cook remains, the battle will be longer, unless political pressure alone pushes other FOMC members to resign. In all likelihood, the White House will have control of the Board of Governors at least by next May, when Jerome Powell's term as Chairman of the FOMC comes to an end. Certainly, following the example of Marriner Eccles, who was replaced as Chairman in 1948 by President Truman but remained a Fed Governor until 1951, Jerome Powell may decide to complete his term as a member of the Board of Governors, which extends until January 2028. Tradition and the weight of political pressure could, however, dissuade him.

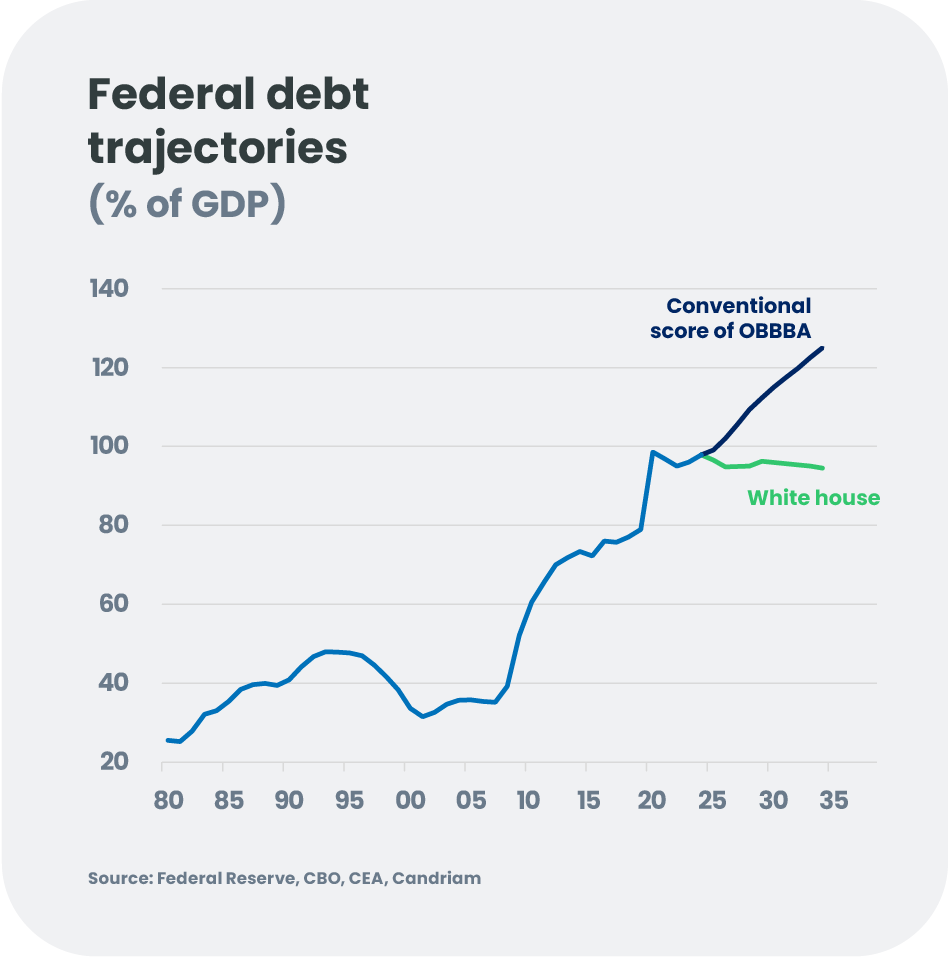

Whatever the decision of the Supreme Court, White House pressure on the Fed is likely to increase in the run-up to the mid-term elections. All the more for another reason, more structural this time, which is likely to reinforce the Trump Administration's determination to see central bank "cooperating" with the Treasury. Contrary to the forecast of the White House economic advisors, the OBBBA (One Big Beautiful Bill Act) is likely to significantly increase the ratio of public debt to GDP over the next few years. The Treasury could, of course, reduce the proportion of long-term issuance and promote stable coins, a large share of which are invested in Treasury bonds.

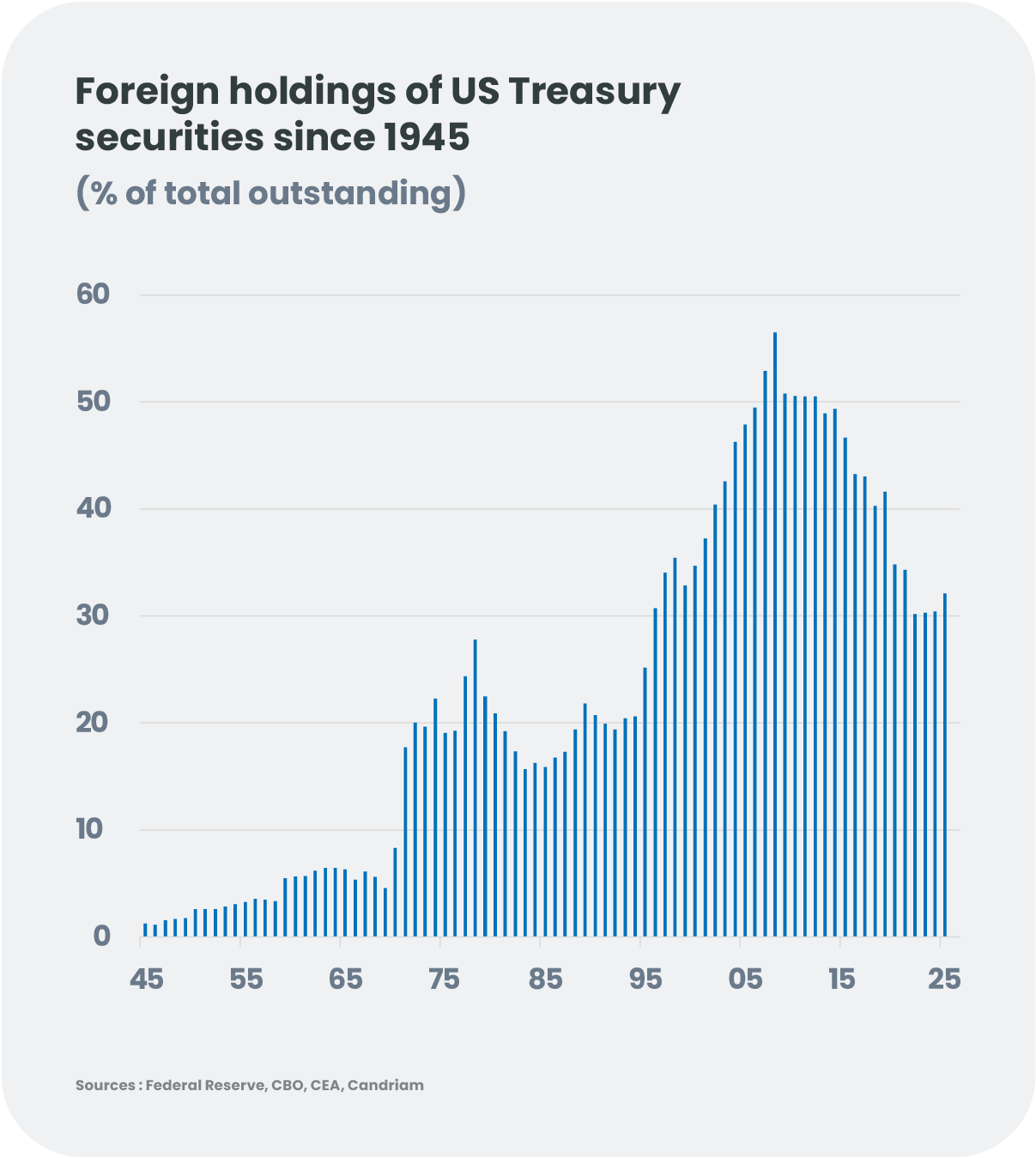

At the same time, the easing of capital constraints already initiated by Michelle Bowman, now head of banking supervision, would make it easier for banks to absorb Treasury securities. The Administration may be tempted to go even further, by introducing 1940-style yield curve control. However, the context is not the same. At the end of the Second World War, US debt was almost entirely held by domestic investors; while today, almost 30% of securities are held by non-residents. A regime of "financial repression" is bound to seriously undermine their confidence.

What might be the consequences for bond markets and the dollar?

For global markets, an erosion of the Fed’s credibility would likely lead to a steepening of the US yield curve by 50 to 100 basis points: short-term yields would fall, reflecting more pronounced expectations of a cut in key rates, while long-term yields would rise as a result of a higher term premium, reflecting growing doubts about the coherence of monetary policy and the central bank's ability to keep inflation under control. However, if the long end of the curve were to slip, the Treasury could reduce the proportion of long-term issues, and the Administration could put pressure on the Fed to target its purchases on this part of the curve.

An " excessive " easing of financial conditions could also be accompanied, if not by an immediate rise in inflation, at least by a rise in inflation expectations, favouring inflation-indexed bonds.

If the Fed's independence were to be called into question, we expect the dollar would be the most vulnerable asset. Among the factors likely to exacerbate this fragility is the currency hedging behaviour of international investors. This mechanism could be particularly effective in Europe, where the dollar exposure of some major pension funds remains close to the highs of the last decade. It should be noted that a weaker dollar would be in line with the wishes of the Trump administration and Stephan Miran, its emissary and now a Governor of the Fed. However, a sudden and steep decline would be less appreciated!

[1] Chairman Ben S. Bernanke, "Central Bank Independence, Transparency, and Accountability", At the Institute for Monetary and Economic Studies International Conference, Bank of Japan, Tokyo, Japan, May 25, 2010.