The world is a strange place right now. Investors are nervous about the US/China trade war while much of Europe is still struggling to sustain growth. At the same time, securities markets are on a tear. US indices for credit and equities are both heading for double-digit returns this year, with the S&P500 up 25% to end-November. With the exception of a few squalls, investors have enjoyed a bountiful ten years of returns.

The weight of uncertainties in the world thus seems to be balanced by a “weight of money”. On Main Street, trade is sluggish to middling and nationalism is on the rise. Wall Street, meanwhile, is buzzing. To explain the paradox, one has to understand the role of central bankers. After the Great Financial Crisis, central banks in key countries and regions decided to pump into liquidity into financial markets with a hope that their largesse would trickle down into the real economy and alleviate a recession. True, recessions have been short-lived. But robust growth has eluded many countries. For asset owners, on the other hand, the effects are clearer and cheerier: the bankers’ double prongs of big bond purchases and aggressive interest rate cuts have pushed pension funds and insurers into riskier investments such as High-Yield debt, private markets and equities while boosting returns everywhere.

But these ongoing interventions of central banks come at a price. Traditionally safe investments, such as government bonds, now yield next to nothing or less. Lend money to Austria for the best part of a 100 years and you will currently be rewarded with a measly 0.7% for the favour. Across the Alps, the benchmark Swiss and German ten-year bonds will earn you less than you put in, as things stand. Bond buyers are paying to lend on approximately one-quarter of the total bond market globally.

This pertains just to nominal yields. Consider inflation and bondholders are losing even more in terms of real purchasing power. Even the benchmark US 10-year bond is a negative-yielder adjusted for inflation (1).

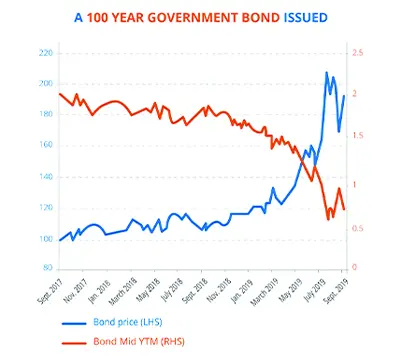

Existing bondholders have boosted their returns thanks to all this yield compression – the chart below on Austria’s 100 year-bond demonstrates this.

But going forward, issuance itself is occurring at negative rates. This summer, Danish bank Jyske issued a 10-year bond at -0.5%.

Some economists have suggested that this could be the new norm; a consequence of an affluent, ageing society. Generations will pay a wealth tax to keep their money safe and live with the loss of capital that comes with buying bonds at negative rates. But two alternatives come to mind. First, affluent investors park their wealth in a bank account, earning meagre interest but not diminishing value. The second is a bunch of strategies that are altogether less influenced by central bankers’ largesse and less vulnerable to market falls.

Investing for the 'New Normal'

These are established alternatives which not only offer greater returns than highly-rated bonds but which also seek to avoid the heavy drawdowns and volatility of riskier credit and equities. They are absolute return strategies such as equity market neutral, global macro, managed futures, risk arbitrage… Developed in the early 50’s,they came to prominence in the aftermath of the tech bubble, when another long bull run ended painfully and left investors belatedly seeking smarter protection.

Globally there is an estimated $3.4 trillion managed in absolute return and hedge fund strategies. Because they characteristically rely little on the direction of markets, the likes of equity market neutral and global macro can generate returns during bull and bear markets. At this juncture in time, such a feature is valuable to asset owners seeking to lower volatility without foregoing capital appreciation altogether.

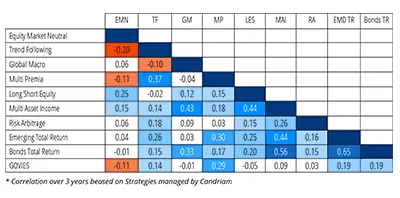

Another appealing characteristic of absolute return strategies is that they show low to negative correlation with not only equity and bond markets but also each other. The chart here demonstrates how Candriam’s own range of absolute return strategies relate to each other.

Example of de-correlated strategies

Statisticians regard only correlations of 0.2 or higher as significant. This diversifying power can be increased even further using our active mix of strategies. This has demonstrated over time a return around 3% over cash with limited volatility and drawdowns.

The value of alternatives is that they rely far more on manager skill than market prices. As such, asset owners need to be sure that manager skill is reliable and persistent. In long-only investing, markets account for a far greater portion of returns than manager skill alone. In absolute return, the opposite is true. After a decade of extraordinary spending by central banks has run up the cost of all assets, it is time for a rethink on how much more markets have to give. Allocation to a lowly-correlated variety of proven manager skills in absolute return strategies, on the other hand, seems prudent and worthy of consideration for investors seeking a middle way between negative yields and the late stages of a bull market in credit and equities.

Candriam has been running absolute return since 1996 with a current suite of 12 diversified strategies, including funds of funds. Sparingly integrated, they allow you to boost the potential return on your bond portfolio and consider 2020 with more confidence.

(1) Using yearly per cent change in core CPI