Is China winning the economic Covid war?

Against both the trade war and the Covid crisis, China has emerged as a domestic economic success. Against the odds it has managed the transition out of the middle income trap where most EM countries founder, climbing up the value-added chain into a consumer-based economy.

A domestic economic success but (not yet) a global economic power, China has become less open economically, and more open financially. But this financial openness remains measured, limited and artificial. Donald Trump dented it seriously, not through tariffs, but by constraining Huawei, the national tech champion.

These developments prompt cosmic questions: How and why does currency becomes dominant? Will the next 'dollar' be a fiat currency? Would investors benefit if the renminbi were to become the next 'almighty dollar'?

Money Printing as a Response to the Covid Crisis

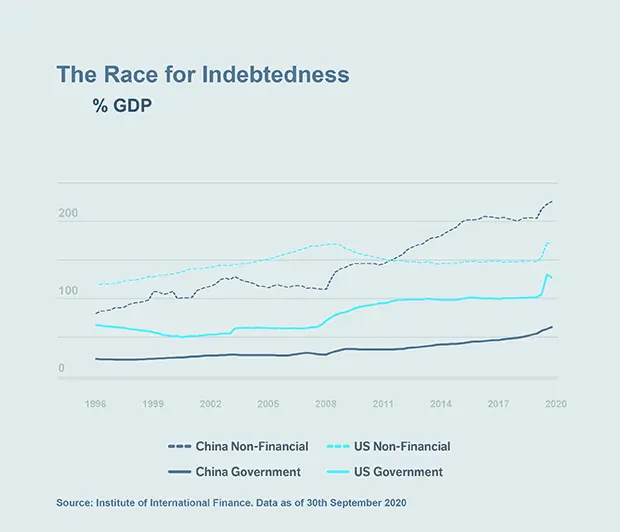

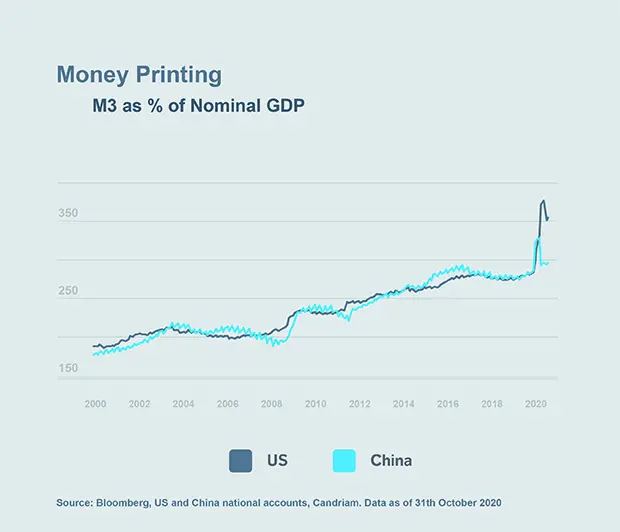

China not only controlled its Covid outbreak early, but also without resorting to printing money. In isolation, this suggests that China is becoming a global currency. Judging by the amount of debt, it is less obvious.

There is only one major currency which did not depreciate vs the US Dollar in March 2020: the Renminbi. Interestingly, the sudden appreciation of the Dollar was caused in part by a liquidity crisis in US interbank markets, dating back to the 2019 unwinding of the Fed's decade of quantitative easing.

The US Dollar: A Lengthy Reign

A currency in the modern sense is nothing more than a government debt which pays no interest and has no physical value. It is a means of exchange and a reserve of value, relying on the network effect and confidence in the issuing state – to some extent, a self-perpetuating characteristic. Even if imbalances accumulate, only a major upheaval will reset the order of things. This has occurred only once in history of fiat currencies, when the British Pound Sterling bowed to the new king, the US Dollar.

Since the end of the gold standard for Sterling, the peak of each national hierarchy of currency has been the central bank. Similarly, one might view the most powerful central bank as the peak of the global system; that is, the Dollar. In normal times the stability of money, or purchasing power, is prioritised, potentially at the expense of the public and of economic growth. During wars and crises the reverse is the case. Governments print money frenetically. During the Covid pandemic, central banks in the US and Europe have thrown themselves into financing the public deficit.

This is how during the early 20th century, Great Britain passed the baton of the leading currency to the United States. The price of the honour was to become a creditor of the world. The Deutsche Mark was a challenger to the Dollar in the decades following the war, but the Euro's built-in frailties meant it could not sustain the inherited momentum towards dominance. Is the Renminbi now in a position to assume a leadership role?

The Hatching of a Global Currency?

China desires to be a global power, but is not unquestionably so. Yet in the face of the worst global pandemic since the Spanish flu, China weathered the pandemic and was the first society to manage a return to a normal life.

The Chinese are known for their steady, painstaking approach. And so 25 years ago China embarked on a journey to open an almost self-sufficient economy towards the deep waters of capitalism. Over the last two years, China has surprised the world, contradicting the view that its growth model relies on high-emission manufacturing, cheap labour, and standardised products.

Becoming a leading currency depends on a nation establishing itself as both the destination and origin of considerable amounts of investment. A leading currency further requires a nation to be a global power, to justify the 'full faith and credit' of the government. To be the dominant currency means that the rest of the world cannot get enough of it. Therefore the underlying superpower will structurally become the debtor of the world, in order to satisfy the demand for the currency.

China remains a decisively closed economy, determined to be an ever-larger creditor. In fact, by recycling their humongous US Dollar reserves, China acknowledges and consolidate the supremacy of the Greenback, and denies a chance to his own currency to become a global means of exchange and reserve.

China is a thing of its own, inspiring awe. But could Xi Jinping have been both the worst and the best thing to happen to China over the last decade? In the twentieth century, the former Soviet Union sent the first man into space, ahead of the US. The Soviet confidence in its own global powers may have strangled any potential openness in Soviet society or economic systems. Might it be because of its lack of openness that the Soviet regime had to bow to he US? For China, could it be that the very political regime upon which its economic success has been built could ultimately prevent it from surpassing the US?

One shivers at China's dystopian use of the most advanced AI technologies to track every individual, social interaction, and small infraction. China is the industrial superpower, well-positioned to become the dominant power in technology.

The development of multiple Covid vaccines in the West is a beacon of hope for the efficiency of non-totalitarian governments. China nevertheless reminds us of a lesson forgotten since the last world war, the need during crises for discipline and efficiency in social and governmental organisation, and the strategic dimension of the manufacturing sector.

Conclusion: Our Money, Your Problem

When the remnants of the dollar-based Bretton Woods system meant the US 'exported' inflation to Europe, Treasury Secretary Connally described the dollar as "our currency, but your problem". Students of economic history will recall the prolonged and painful depreciation which followed. Japan also paid the price of blind faith in the greenback, when years of current account surplus invested in the United States was vaporised. The vicissitudes of history have often forced finance and trade people to turn towards a currency, when other options run out – often through a sudden dramatic crisis.

It is not a rational investment strategy to predict a structural winner in currencies.