The current inflation trend is unique to the post-COVID economy: part of the latest round of inflation is the result of supply chain disruption and part the result of pent-up demand from consumers eager to avail themselves of goods and services of which they were deprived during the pandemic. These pressures will likely prove temporary. The questions dogging central banks, however, are what will happen to wages… and when and by how much will they need to tighten their policy?

Global industrial recovery, supply chain disruptions and base effects have fuelled inflation

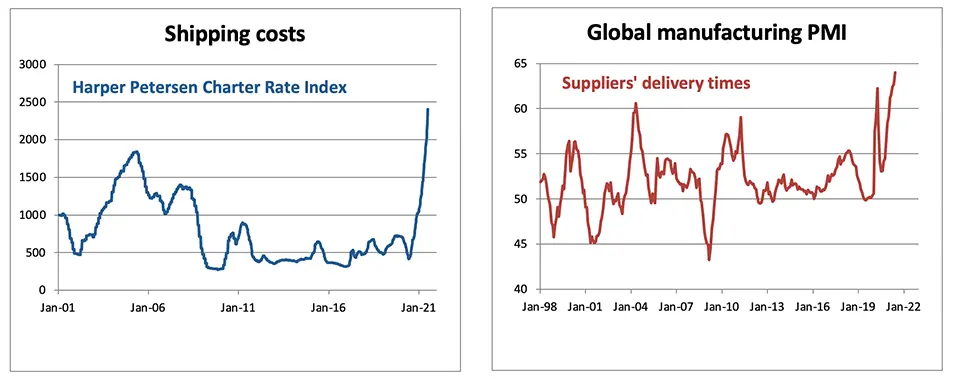

Over the last twelve months, inflation excluding food and energy reached 3.8% in the US, its highest level in nearly thirty years. This particularly rapid pace of price increases should come as no surprise. The pandemic can be seen as a temporary shock that interrupted economic activity but left demand broadly unchanged (thanks to government support). As a rule, once such disasters are over, demand recovers quickly. Yet, while the pandemic has left overall production capacity roughly unchanged, the global economy has been disorganized and supply chains seriously disrupted: shipping costs have skyrocketed, commodity prices have soared, ... and the global shortage of semiconductors shows no signs of abating (nor is it expected to before Q1 2022)! As a result, the functioning of the supply chains in place before the pandemic has been seriously impaired, leading to a significant increase in suppliers’ delivery time. This disorganization is temporary in nature, but will take some time to resolve1.

While the contraction in global industrial production was the same than during the Global Financial Crisis, the rebound was much stronger

Supply chains disruption has led to a significant surge in supplier delivery time.

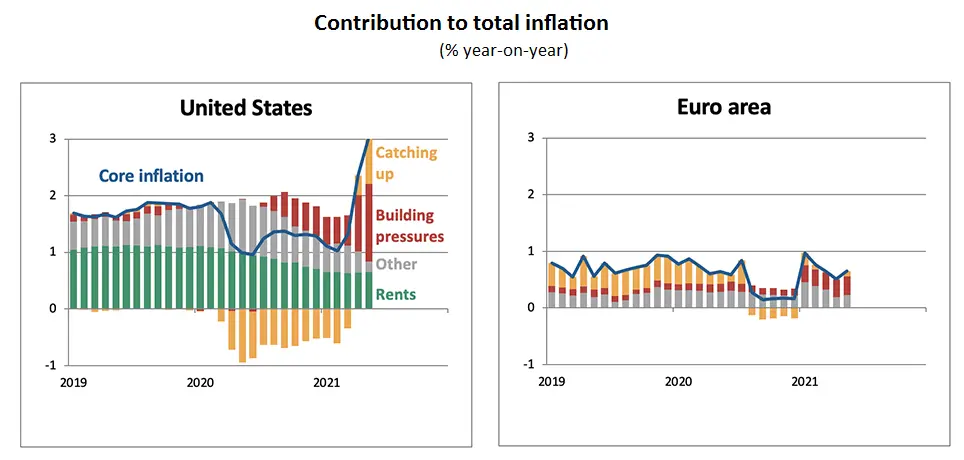

Recent developments in consumer prices have shed some light on the dynamics at play. Over the past two decades, inflation has been driven largely by services, with global competition and the globalization of supply chains weighing on goods inflation. However, since the onset of the pandemic, goods inflation has significantly ramped up, while services inflation has been muted. This is because the pandemic has temporarily distorted the structure of demand in favour of certain goods (sporting goods, furniture, used cars, etc.). Coupled with supply chain disruptions, these goods have seen their prices rise sharply. Some services have also been indirectly affected. Car rental prices, for example, have risen more than 60 percent since February 2020: during the pandemic, rental companies were forced to sell part of their fleet to survive; they are now struggling to replenish it to meet demand. But, overall, services inflation has been muted as the pandemic have particularly weighed on consumption of services. Prices of "non-essential" services (air transport, hotels, etc.) have thus plummeted during the pandemic. As the economy reopens, though, these prices are starting to catch up and will likely continue to do so. There are, therefore, good reasons for inflation remaining under pressure for several more months. However, while inflationary pressures might be more long-lasting than some thought, this rebound can reasonably be regarded as temporary.

In the euro area, while similar dynamics are at play, inflationary pressures have so far been much more limited, as this region’s recovery lags the United States and inflation was initially more muted: at the end of May, while core inflation was approaching 4% in the United States, it was still below 1% in the euro area. Admittedly, inflation has accelerated in a handful of countries that have weathered the crisis better than others. But, even in these countries, the surge has been limited, while in the hardest-hit countries of southern Europe, inflation remains much more depressed than before the crisis.

Accumulated excess saving could push demand slightly above trend in the US

Beyond these temporary effects, though, the strength of the recovery is unprecedented and the rapid rise in demand is raising fears of a sustained acceleration in inflation. This is notably the case in the United States, where household income was not only preserved (as was the case in the euro area), but has been considerably increased by fiscal support. As a result, households have been piling up a significant amount of savings.

What if, tomorrow, the extra savings potential generated during the pandemic were to be spent in full? Much of it, it should be noted, has probably already been used by low-income households in particular to pay down debt but also rent arrears. Some of those extra savings, though (more than $1 trillion), is in the hands of the wealthiest households, who, for more than a year, have not been able to buy as many "non-essential" services as they used to. They may now want to catch up. A simple calculation, however, makes it clear that this would be difficult. If households were to decide to spend $1 trillion to buy the services they were deprived of during the pandemic, total consumption of these services would be pushed 30% above their pre-crisis trend: this seems implausible. It is more likely that not all of these savings will be spent (and will continue to fuel mainly purchases of financial assets... or real estate): our main scenario assumes that approximately a third of the $1 trillion extra savings related to under-consumption will be spent.

In the euro area, some “extra savings” have also been accumulated during the pandemic… but to a much smaller extent. As a result, excess demand is much less a concern for the euro area, where we expect the recovery to be complete at the earliest by the end of 2021 for some core countries, but not until the end of 2022 for others.

All in all, activity could be pushed above its pre-crisis trend in the United States, as households spend part of the extra savings accumulated during the pandemic, but the likelihood of such a scenario in Europe seems more remote. Moreover, focusing on inflationary pressures in the short term misses the point: for inflationary pressures to be sustained, wages and productivity developments are essential.

Above-trend demand does not necessarily mean above-trend employment

In the US, by the end of May, the wage drift was already spectacular in some sectors: at an annual rate, hourly wages had risen by more than 15% since March in the leisure services sector and by almost 10% in the retail and transport sectors. But this owes much to the fact that, when economies reopen, hiring needs become very elevated in some sectors … while some people may be more reluctant to engage in such in-person – and generally low-paid – jobs (incomplete school reopening, worries about the virus, generous unemployment benefits, …). Most of these are temporary mismatches that will gradually dissipate as the vaccination gains traction, schools reopen and the generous unemployment benefits enacted during the pandemic come to an end (25 states have already decided to end these programmes while the rest will soon follow, with their scheduled for early September). These microeconomic tensions should not blur the big picture: employment is still 7 million below its February 2020 level. Against this backdrop, it is difficult to expect sustained and broad-based tensions on the labour market.

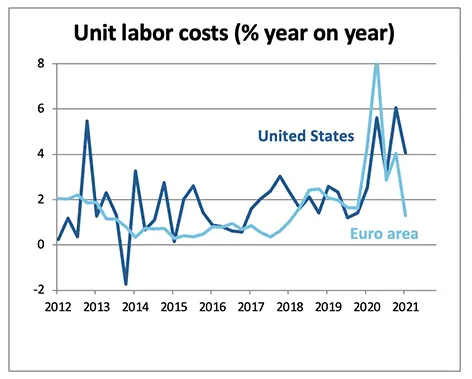

It is all the more so unlikely given that productivity has recently accelerated. While it is cyclical for a large part, this increase in productivity gains started before the pandemic as firms had been significantly increasing their investment efforts not only in equipment, but also in intangible investments such as R&D. On top of that, it cannot be ruled out that, by accelerating the pre-existing trends of automation and even more so of digitalization (remote working, e-commerce, …), the pandemic will contribute to faster productivity gains over the next couple of years. For inflation, such gains are key in two respects: a given level of output could be achieved with fewer workers, which would dampen tensions on the labour market and therefore on wages; this would also help firms preserve their margins, as it would reduce their unit labour costs.

In the euro area, short-time work schemes were key in limiting the unemployment surge. In this context, the unemployment rate provides a misleading measure of slack on the labour market. Employment rates are, in this respect, much more reliable. In southern Europe, younger cohorts have been particularly affected by the pandemic. Even before it, men’s prime -age employment rates were still far from their mid-noughties levels and the pandemic has again pushed them lower, especially in Spain and Italy. With significant slack on the labour market, wages have little reason to be under pressure in the euro area.

Ultimately, inflation is in the hands of central banks

The change in the Federal Reserve monetary policy framework may have raised concerns about its tolerance of inflation. Indeed, under its new Flexible Average Inflation Targeting framework, the Fed will temporarily tolerate higher inflation in compensation for falling short of its target before. The shift to an inclusive employment target could also have added to concerns. But neither (nor both taken together) means that the Fed will sit back and watch inflation rise without taking action. Of course, while such action would help keep inflation in check, it would not be without risks to growth.

The Eurozone is facing some of the same challenges as the US but in a much less acute form. Before the pandemic, the area was facing too-low inflation and its recovery lagging the US. Concerns over the ECB’s upcoming monetary policy review, which could lead to a profound change in its inflation stance, are also misplaced. Whatever changes are decided, they will not jeopardize the ECB’s commitment to keeping inflation low.

1 On June 8, the White House announced the creation of a task force targeting supply chain shortages and resulting inflation.