In the past: a particularly profitable environment

In recent years, sluggish global growth and low interest rates have encouraged companies to use debt as a means of financing their development. Debt has enabled companies to invest in R&D in order to boost sales or adapt to a new environment and also allowed them to achieve their strategic goals more rapidly through mergers and acquisitions.

As profitability targets expected by shareholders cannot always be reached through growth alone, debt has also been used massively to finance share buybacks and to distribute exceptional dividends.

Optimising the profitability of deployed capital in this way has been largely inspired by the accommodating monetary policy adopted by the central banks and the implementation of non-conventional measures such as quantitative easing (QE) by the European Central Bank (ECB) or quantitative & qualitative easing (QQE) by the Bank of Japan (BoJ).

Broadly lower interest rates have considerably reduced interest servicing charges among companies. This environment has also led to diversification in financing sources for smaller businesses by providing easier access to bond funding for many companies. What has been the result? For certain companies, this has meant a reduced debt burden and a lower chance of bankruptcy, whereas for others it has facilitated development projects.

Present day: a record level of debt?

Has the maximisation of companies’ balance sheet structures through borrowing, rather than building up shareholders’ equity, deteriorated their creditworthiness?

According to the International Finance Institute (IFI), total corporate debt excluding the financial sector currently represents 91.4% of global GDP, i.e. an increase of 20 points over 20 years. This figure should be viewed in perspective, however, as the data relate to gross debt which does not take into account the increase in value of corporate assets.

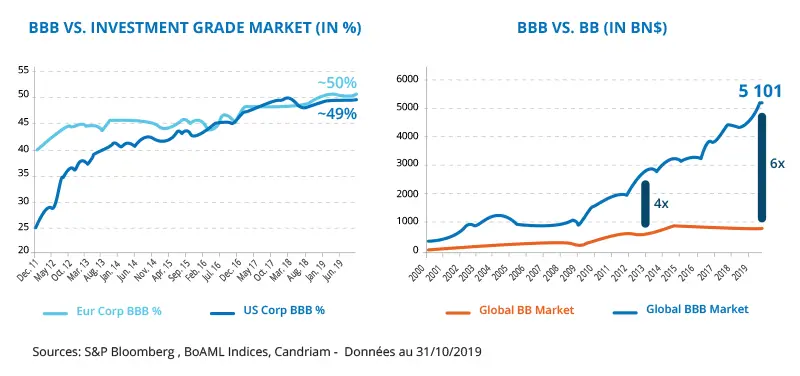

It is nonetheless a fact that, during the past 8 years, the proportion of BBB-rated issuers in the US market has risen from 40% in 2011to 50% in 2019, while the European market has seen an increase from 25 to 50% over the same period. What has been the consequence of this increase? BBB-rated debt now represents 5,100 billion dollars globally, which is 6 times more than in 2000.

Overall debt ratings have therefore deteriorated significantly over the past few years. But does this mean that there is a credit market bubble?

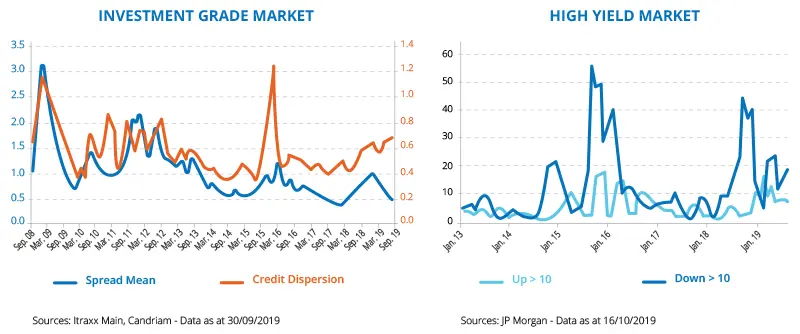

Not really. In our opinion, the current high level of credit market dispersion is primarily a reflection of increasing idiosyncratic risk. Specific difficulties encountered among debt securities appear to have a relatively muted knock-on effect on the rest of their particular business sector and only a limited impact on credit spreads. Furthermore, although the ratings agencies estimate that the proportion of potential fallen angels, i.e. companies downgraded from an investment-grade rating (BBB) to high-yield status (BB or lower), should rise to represent over 20% of the total current BBB market, we believe that this risk is overestimated. Abundant liquidity and the high premiums currently paid among private equity acquisitions targeting non-listed companies encourage the divestment of subsidiaries and assets and provide many companies with the opportunity of reducing their debt levels and therefore to maintain their investment grade category ratings.

The future: towards more responsible debt?

This is a fact. The purely financial approach adopted by companies is being brought increasingly into question. Investors now expect companies which are key players in the economy and broader society to integrate environmental, social and governance responsibility (ESG).

The social pressure on companies, coupled with financial performance constraints, obliges them to adapt, despite their huge financing requirements, particularly in terms of energy transition.

The automotive sector can also be considered in this light, with vehicle electrification involving heavy financing requirements for R&D and production line renewal. Similarly, the utilities sector will require high levels of funding for decommissioning coal power stations and the switch to renewable energies.

It would be a mistake to disregard extra-financial factors. Companies neglecting to do so could see investors refusing to finance them or only granting funding at prohibitively high costs which could undermine the profitability of their investments and therefore their long-term viability. On the other hand, financing requirements increase the level of companies’ debt, which is a potential source of ratings downgrades by the agencies.

Looking forward, selectivity is required, including the integration of a rigorous ESG approach. This approach should lead to investments in the winners during the global transformation phase, by avoiding companies with a less certain future. A world of opportunities is opening up to us.